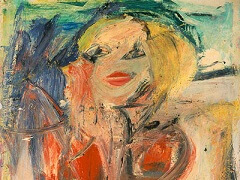

Woman with Bicycle, 1952 by Willem de Kooning

By the 20th century, the human body was being disassembled and re-assembled by painters of the various avant garde schools to an almost wild and frightening degree. You can almost hear the

uproar as they did all that metaphorical sawing and hacking. This was the century of the uncalm, the feverishly experimental, the moment when the terrible undercurrents rose up and

overwhelmed the surface.

Is this what Freud, Nietzsche and two huge, murderous bouts of warfare - to name but three tentative explanations for all this wilful painterly disorder, this arrant refusal to accept the

testimony of the human eye - had brought us to? Whatever the explanation, the human form began to resemble tomorrow's new model as it is tinkered and messed with on its slow passage through

the Nissan factory. That is not an entirely satisfactory analogy - there is no sleek and clean-lined conclusion to this painting.

Instead, we feel that the body itself, this staring-eyed female form, is no longer quite singular and whole. It is not undeniably self-contained. It is not even of and for itself. It has

loosened the grip of reasonable self-control - and so has its making. It's a joyous, messy patchwork of hectic gesturings. There is no easy contemplation of the surface, no celebration of

the essential symmetry of the human form. What Da Vinci created in his great drawing of

Vitruvian Man, those long centuries of thought which had led to the conclusion that man was somehow aligned with the divine

order of things - or, at the very least, divine orderliness - no longer seems to appertain. There is no longer any way in which de Kooning's woman is underpinned by any notion of harmony or

universality. She is out on her own, staring at us, bulbous-eyed, in all her colourful raucousness, utterly unruly, bursting apart at every seam. And she is alive within a general context of

painterly unruliness - the brushstrokes of this painting power off in so many different directions.

In fact, she looks like a precarious agglomeration of parts. If this were music, it would be a simultaneously cacophonous rendition of Schonberg and Webern. It seems shrill and hyper-active,

almost at war with itself - a jagged, terrible, extreme example of grotesquerie. Did Pablo Picasso light the touch paper? In 1909, he certainly

committed unspeakable acts of violence to the depiction of the female form in Demoiselles D'Avignon. Forty years on, de Kooning,

painting in New York, seems wilder still. This painting is one of a series of many ferocious attempts to render the female form. We feel this painting had no easy beginning and no easy end -

more exhausted abandonment than anything you could call an end.